Translated by Fernanda Miguens

This writing is dedicated to Professor Robert Harrison, as a gesture of gratitude for his lessons in Dante’s Inferno.

meu bem

sensual maquinário crepuscular

perdi a chance dalgum punhal

de amor traído, de susto, de bala

ou vício. nada é divino e arde

o fogo de conhecê-la. tome um

gole de cerveja no copo em que

outros cantores chamam baby

você precisa saber, sou a piscina

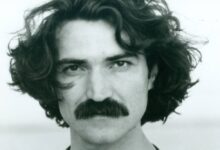

Adriano Menezes para Belchior

enquanto ele morria.

Read Canto V of The Divine Comedy by Dante and see how he walks next to Virgilio through the Second Circle of Hell. We are talking about a circle of lovers who were condemned to hold together. They have no autonomy over their destinies. They are raptured and engulfed by a strong wind. And the desire that condemned them to sorrow held the same qualities. [I make a brief stop. I have always found it curious that the windy weather was a condition of the lover’s suffering in Dante’s poetry. In the Yoruba tradition, Iansã is the name we give to the Goddess who possesses the storms and rays in the sky. She governs fire, winds and the sweeping passions. She is the only orixá which can descend into hell, facing and dominating the Eguns, who are the spirits of the dead]. On his journey, Dante gets together with Francesca de Rimini to listen to her sad love story:

‘Amor, ch’a nullo amato amar perdona,

mi prese del costui piacer sì forte

che, come vedi, ancor non m’abbandona.

Amor condusse noi ad una morte.

Caina attende chi a vita ci spense.’

Queste parole da lor ci fuor porte.[1]

Francesca was induced by the reading of Galeoto when she fell in love with Paolo. And when her husband found out about what was happening he killed them both…

Dante is upset to hear that sad story. He also feels the grief and the pain of those who are fading to death.

After leaving the monastery of the Capuchin Friars in Serra de Guaramiranga, Belchior returned to visit his friends. It was during these visits that he shared with one of his colleagues the desire to “isolate himself to translate the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri into popular language.”[2] The presence of the Florentine poet in the words of his songs was never a coincidence.

In his Divina Comédia Humana Belchior sings a love song that blossoms from a casual encounter. However, as a psychoanalyst friend warns him: one can not really be happy that way “because love is a deeper thing than a sensual thing”[3]. Belchior doesn’t care. He puts depth aside. He wants to dwell on the skin of his beloved, heaven and hell. For Belchior, existence is sung by its own transience. He is in a hurry, has urgency and “any space, body, time or manner of saying no”[4] is also a reason why he exists. His denial of the advice of the psychoanalyst friend evokes and defends love as a necessary damnation. This is the Amor de perdição that gives the name to one of his songs. As it happens in Dante – “amor condusse noi ad una morte” – Belchior sings that love that could be no less than an experience that lead us to die and descend into hell.

The body, the risk, the fury and the proximity to death are the fundamental conditions for his Coração Selvagem. In one of his greatest hits he sings: “meu bem, come and die with me”[5]. He does not want the thoughts in his head. He is in the hurry of wanting a body. But he spends some time in the body that he finds, he falls in love in a slow embrace. There is the kiss and the music that plays on the radio. (Baby is the song).[6] This is how your loved one (meu bem), “that other singers call baby”[7], sees the other closely and plunges into his loneliness.

In Brasileiramente Linda, Belchior explains of what kind of love he is talking about. Love is a trivial thing. He seeks for the “fundamental passion; the vulgar passion of Oedipus to invent his own be[ing]”[8]. The substance of this sung passion is human in what it can share with the intensity of the animal: it is when we almost forget the idealization of the other. An almost anthropophagic gesture of devouring the other as much as we can without any shame.

Although Belchior was one of the most universal Brazilian singers, especially on poetics, this passion that evokes death is sung from a Retórica Sentimental of the encounter “made of three sad races”[9]. This passion is tied to the Brazilian “sad tropics”[10]. In the same land that he exposes with irony in Jornal Blues, “the bishop and the ruler, old Catholics, young politicians, ladies of middle age”[11] do not seduce themselves by “the common good”[12]. Those “respectable citizens”[13] that control our lives “are needed and envied in Dante’s Inferno”[14]. God, this “Brazilian thing, patient in a Northeastern way”[15] does not inhabit hell. Belchior wants paradise just like Dante.

[I stop once more. If Iansã, on the one hand, is the orixá of the passions that hit men like a lightning or a hurricane that can suspend us from the ground, on the other, she is the one that descends to hell and controls the Eguns. This descent into the underworld can be allegorically associated with the loss of ego control. It is about a certain collapse in the attempt to harmonize desires with reality. But after a confrontation with the instincts it is possible to master those desires and get out of hell. I’m thinking of Carl Jung’s statement: “O homem que não atravessa o inferno de suas paixões também não as supera[16]”.]

“No começo era o amor[17]”. It is from love, as a fault that we offer, that psychoanalysis is born for Lacan. If love is composed of desire (an infinite capacity of imagination) and by the physical component (sexual act), unable to accomplish all that desire projects, psychoanalysis aims to make man accept his daily misery because all suffering emanates from the infinity capacity of the desire to produce expectations that can not be realized by the sexual act. If satisfaction belongs to the order of the impossible and we need psychoanalysis to deal with this frustration, Belchior wants to live with the anguish of aspiring to the fullness of the imagination produced by lust, while admitting the impossibility of desire. And he makes that choice by rejecting the analyst’s advice in the Divina Comédia Humana song. As far as this theme is concerned, it does not matter what love is in itself, but what it is capable of producing.

But what is the existential implication of knowing about love? For Belchior, if “living is better than dreaming”[18], love is one of the conditions to experience and face reality as it is. Just as he sang in Apenas um rapaz latino americano: “do not worry, my friend, with the horrors that I tell you. That’s just a song because life, life is really different, life is much worse”[19]. But what does this have to do with Belchior’s path to Paradise?

In the song Que tudo o mais vá para o céu (Everything else to go to Heaven), witch he wrote in partnership with Jorge Mautner, the opening for his album Paraíso (1982), follows a scene in which the lyrical self remembers in detail a conversation that seems to occur during a meal with the beloved in Andaluzia and Valladolid. They talk about daily things. She said that Granada was overseas, in Spain. While dipping a piece of her bread into his wine she also talked about thigs happening in Brazil, the International Monetary Fund… And the subject ended on Guernica, a painting by Picasso on the Spanish Civil War, which was responsible for the coward execution of the poet Garcia Lorca by an army of Franco’s fascism. The couple is talking about the Andalusian poet.

“Go way poète maudit! Your cursed time has already ended!”.[20] It seems that the meeting was interrupted with insults by the “man of the machine”[21].The verses follow as an allusion to the extermination of the Poet and also to the own Belchior that felt the collapse of its success in the seventies. However, he “left without caring about anything”[22]. And the secret that made him ignore the insult “was to have a soul in love”[23]. In any case, this state of satisfaction does not last long. Her black hair, darker than the “Graúna’s wing black”[24], makes him dive into reality. He feels the weight of the night and tries to escape the loneliness that has invaded him. He enters a movie theater in Technicolor and Pana Vision, but he asks himself: “What good is my playboy life worth?”[25]

The immediate reference to the music of Roberto and Erasmo Carlos Quero que vá tudo para o inferno (I want everything to go to hell) was a provocation to the best-known Brazilian singer, who was popular for his love songs. In the song of the Jovem Guarda icon the lyrical self suffers the absence of the woman he loves and, because of this, his “life as a playboy” is not enough to fill the pain and loneliness that his absence produces. Everything else is irrelevant. Everything else could go to hell. Belchior’s provocation rests on elements and disputes related to music industry in Brazil that are not relevant here.[26] My interest is the provocation in what refers to the form of love that music evokes. In the song of Erasmo and Roberto Carlos what matters is if the lyrical self possesses his beloved one, “what exists in addition”[27] does not matter. When it comes to Belchior the beloved becomes a space for the experimentation of the loneliness that hurts him. What is around him, even with the anguish he feels, matters to him, and he wants, despite of his pain, that “everything else to go to Heaven”[28].

Belchior’s provocation to the kind of love present in Roberto’s music, within certain limits, is also a criticism of a cordial ethos ruled by the selfishness that finds its place in Brazilian hell. Belchior was considered annoying. This happened because his songs – even when they spoke of love, passion and casual sex – did not fail to show missing colleagues, the expatriated and all the danger around the corner determined by the dictatorial political condition. The experience of love does not alienate him from the world, for it is precisely in the presence of the woman he loves that he remembers the executed poet. In Meu Cordial Brasileiro, a partnership with Toquinho, he confesses that he has no patience to inhabit the tropical version of Dante’s Hell: “Forgive me for not being in good shape, and for losing my sense of humor, before these indecent people, who eats sleeps and consents, which is silent, then is alive”.[29].

But Belchior is not responding only to Roberto. In a more radical way, it is with Caetano that he speaks. (I use the poetic license to invent a very real dialogue between Belchior and Caetano where they mention their own songs as well as some of The Beatles and Rolling Stones). It is the “old bahiano composer”[30]” who begins the conversation.

– Baby, you need to know about the pool. Baby, you need to hear that song from Roberto. Baby, you need to learn English. Baby, you need to know about me. You need to learn what I know and what I don’t know anymore.

– Sorry sorry sorry sorry, baby! I’m sorry if my English came from the music calendars of the month. But you need to know, because as you told me once… Everything is dangerous. Everything is divine and wonderful. Sorry sorry sorry sorry, baby, because you told me once… Here comes the sun. I need you because you told me once… Every pleasure comes from the body.

– Baby, read on my shirt!

– I can’t get no satisfaction.

– Baby, I know things are like this.

Belchior’s passion is a critical and melancholic heritage of Tropicalia. It was above Bahia, in this invention we call the Northeast (“The Northeast is a fiction! The Northeast never existed!”[31]), that he produced according to his own ambitions. But Belchior does not want to talk about the things that he learned on the tropicalist records because it was while listening to them that he heard: “Attention! When you turn a corner you find a joy” [32]. Belchior wanted to sing what he lived. Not what he had planned. He knew that “Love was a good thing [33]”, but he also knew that “any song is worse less than the life of any person [34].” It was they, the cordial Brazilians, who won again! “Take care, meu bem, there’s danger on the corner.”[35] How was it possible, after they have done everything they did, that they were still the same, that they and still loved like their parents did?

But Belchior sought Paradise as well as Dante. Both in details and in hallucinations about reality. “Why, you say you hear the stars, have you lost your mind?”[36] And when he was in the heaven he had the vision of “l’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle”.

E ainda ponho a camisa

Que avisa, precisa:

“I can’t get no satisfaction!”

Oh! Oh! Bad bed times!

Onde os puros saberes?

Onde a fúria de seres humanos

Contra a ira dos deuses?

Oh! Que cena obscena!

Pedir: “Por favor, nada de amor!”

“I can’t get no satisfaction!”

Belchior – Elegia obscena

***

The soundtrack of this text can be accessed at Spotify:

Belchior. “Divina Comédia Humana”. Todos os sentidos. Warner, 1978.

Belchior. “Amor de perdição”. Elogio da Loucura. Poligram, 1988.

Belchior. “Coração Selvagem”. Coração Selvagem. Warner, 1977.

Belchior. “Brasileiramente Linda”. Era uma Vez um Homem e Seu Tempo. Warner, 1979.

Belchior. “Retórica Sentimental”. Era uma Vez um Homem e Seu Tempo. Warner, 1979.

Belchior. “Jornal Blues (Canção Leve de Escárnio e Maldizer)”. Melodrama. Polygram, 1987.

Belchior. “Apenas um rapaz latino americano”. Alucinação. Phonogram, 1976.

Belchior e Jorge Mautner. “Que tudo o mais vá para o céu”. Paraíso. Warner, 1982.

Erasmo Carlos e Roberto Carlos. “Quero que vá tudo para o inferno”. Jovem Guarda. CBS, 1965.

Belchior e Toquinho. “Meu Cordial Brasileiro”. Era uma Vez um Homem e Seu Tempo. Warner, 1979.

Caetano Veloso e Gilberto Gil. “Divino maravilhoso”. Gal Costa. Phonogram/Philips, 1968.

Caetano Veloso. “Baby”. Tropicália ou Panis et Circencis. Philips Records, 1968.

Belchior. “Sorry, Baby”. Single. Chantecler, 1973.

George Harrison. “Here comes the sun”. Abbey Road. The Beatles. Apple Records, 1969.

Mick Jagger e Keith Richards. “(I can’t get no) satisfaction”. Out of Our Heads. The Rolling Stones. London Records, Decca Records , 1965.

Belchior. “Conheço meu lugar”. Era uma Vez um Homem e Seu Tempo. Warner, 1979.

Belchior. “Como nossos pais”. Alucinação. Phonogram, 1976.

Augusto de Campos e Péricles R. Cavalcanti. “Elegia”. Cinema transcendental. Caetano Veloso. Verne, 1979.

Belchior. “Elegia obscena”. Elogio da Loucura. Poligram, 1988.

____________________

NOTES:

[1] “Love, which pardons no one loved from loving in/ return, seized me for his beauty so strongly that, as/ you see, it still does not abandon me. / Love led us on to one death. Caina awaits him/ who extinguished our life.’ These words were borne/ from them to us.” ALIGHIERI, Dante. The Divine Comedy. Edited and Translated by Robert M. Durling. Vol. 1 Inferno. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 90-91.

[2] MEDEIROS, Jotabé. Belchior. Apenas um rapaz latino-americano. São Paulo: Todavia, 2017, p. 19.

[3] “Porque o amor é uma coisa mais profunda que uma transa sensual”.

[4] “Qualquer espaço, corpo, tempo ou forma de dizer não”.

[5] “Meu bem, vem morrer comigo!”

[6] The song “Baby” written by Caetano Veloso and performed by Gal Costa on the album Tropicália or Panis et Circensis, released in 1968 was one of the greatest Brazilian hits. Baby is a song about pop culture and consumer culture in the late 60’s and was quoted by Belchior a few times in his songs.

[7] “Que outros cantores chamam baby”.

[8] “Paixão fundamental, (edípica vulgar) de inventar [s]eu próprio ser.”

[9] “Feito de três raças tristes”.

[10] “Tristes trópicos”.

[11] “O bispo e o governante, velhos católicos, políticos jovens, senhoras de idade média.”

[12] “Bem comum”.

[13] “Cidadãos respeitáveis”.

[14] “Fazem falta e inveja ao inferno de Dante.”

[15] “Coisa brasileira, nordestinamente paciente.”

[16] “A man who has not passed through the Hell os his passions has never overcome them.”

[17] “In the beginning there was love.”

[18] “Viver é melhor que sonhar.”

[19] “Não se preocupe, meu amigo, com os horrores que eu lhe digo. Isso é somente uma canção, a vida, a vida realmente é diferente. Quer dizer, a vida é muito pior.”

[20] “Vai embora poeta maldito! Seu tempo maldito também já terminou!”

[21] “Homem da máquina.”

[22] “Eu fui embora sorrindo sem ligar para nada.”

[23] “Era ter a alma apaixonada.”

[24] “Negro da asa da graúna.”

[25] “De que vale a minha boa vida de playboy?”

[26] SANCHES, Pedro Alexandre. Como dois e dois são cinco. Roberto Carlos (& Erasmo & Wanderléa). São Paulo: Boitempo, 2004 p. 231-243.

[27] “O que de mais existe”.

[28] “Tudo mais vá pro céu.”

[29] “O Senhor não me perdoa eu não entrar numa boa e perder sempre a esportiva, frente a esta gente indecente, que come, drome e consente; que cala, logo está viva.”

[30] “Antigo compositor baiano”.

[31] “Nordeste é uma ficção. Nordeste nunca houve.”

[32] “Atenção! Ao dobrar uma esquina, uma alegria”.

[33] “O amor era uma coisa boa”.

[34] “Qualquer canto vale menos do que a vida de qualquer pessoa”.

[35] “Cuidado, meu bem, há perigo na esquina”.

[36] “Ora direis, ouvir estrelas, certo perdeste o senso.”

______________________

Imagem: Virgílio e Dante observam as almas condenadas pelo pecado da luxúria sendo carregadas pelo vento. No primeiro plano, Paolo e Francesca.Ilustração de Gustave Doré (séc XIX).

vc_row]

ABOUT AUTHOR

No comments